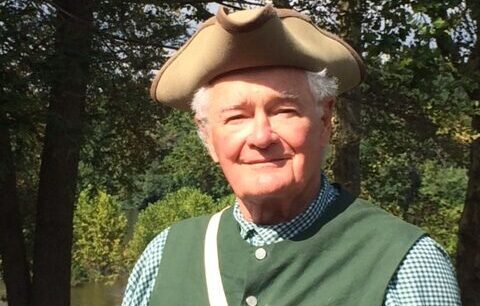

Meet Tom Maddock

You can’t go home again, at least according to the title of Thomas Wolfe’s literary classic. Maybe not, but then the acclaimed novelist never met Thomas Maddock II, who has come about as close to doing that as you possibly can.

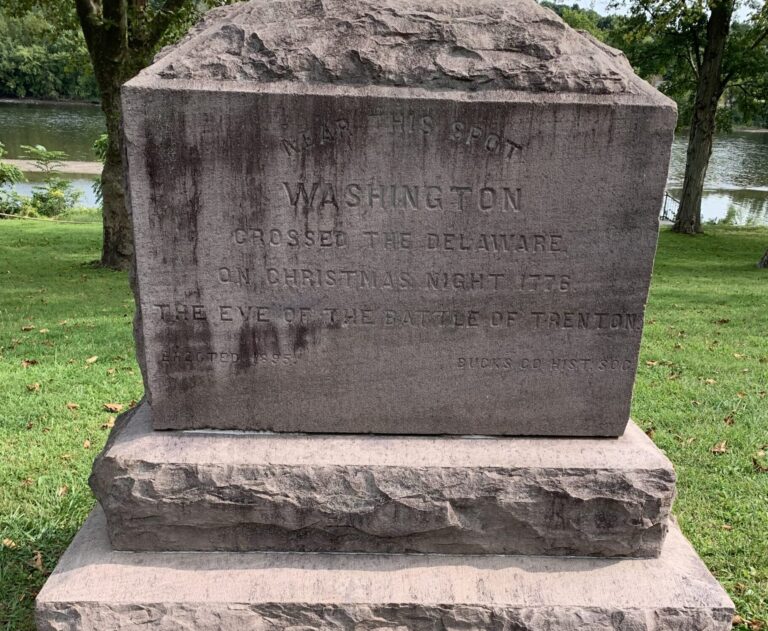

Tom was born in Trenton, NJ, in 1936 and spent the next fifteen years living in what is commonly referred to as the McConkey’s Ferry section of Washington Crossing Historic Park (WCHP)—the site of the Continental army’s legendary 1776 Christmas night crossing—before his family moved to Ewing Township in 1951. A Ewing High graduate, Tom earned a B.A. in history from Haverford College in 1958 and spent six months on active duty in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. He then entered into the fine paper business and over time was employed in sales, marketing, business development, recruitment, and management. Tom’s career took him to North Jersey where he raised a family, but in 2002 he returned to Bucks County, married his second wife Bunkie—now a fellow interpreter at WCHP—and would subsequently begin giving guided tours on the grounds of his boyhood home.

When the Friends of Washington Crossing Park (FWCP) organized in 2010, Tom became a FWCP historical interpreter, and he has been devoting himself to that endeavor ever since. As he puts it, “I have been able to complete the circle.” Tom’s many contributions to the FWCP and WCHP have included, but are not limited to: giving tours at the park’s different sites, reading the Declaration of Independence at public gatherings on July 4, giving talks about Washington’s military leadership to various groups, providing media commentary for the annual re-enactment of the 1776 Christmas night crossing, leading youthful visitors in musket and cannon drills, serving customers in the visitor center’s gift shop, and soliciting sponsor ads for the park’s annual program booklet. Along the way, he has mentored a slew of other historical interpreters at the park (yours truly among them).

Q and A

Tom has agreed to share some thoughts on his experience and issues relating to the work of the Friends organization and the historical-education programming at the park:

What was it like living in WCHP as a boy? What is most memorable about that experience? What did this site look like? Did you appreciate its historical significance back then?

The park in which I grew up was very different than today. There was no visitor center, and no other public buildings or walking trails. Life was very simple in those days. My siblings and I had to create our own games and entertainment. We played “Cowboys and Indians,” rode our bikes, and frolicked in the backyard until it was time to come inside, where we would listen to the radio before dinner. We had no TV. Bedtime was at 7:30 every night.

Family outings were few and far between. Each Sunday after church, we would take a family walk, which turned out to be wonderful. It was something to look forward to every week. We did not do much with sports because there were so few kids. I never played a team sport until I was a high school sophomore. Our early schooling was in a two-room, eight-grade schoolhouse with just two teachers. I spent my sixth and seventh-grade school years in a one-room schoolhouse with one teacher and outdoor toilets. Given this background, my parents were very proud that four of us graduated from college.

As an adult, visiting the park has always brought back very special memories. We grew up knowing about the history of the Crossing, but our parents did not spend any time discussing its historical significance with us. My memories of growing up here are very positive. Given the circumstances, I had a very happy childhood and developed a special bond with my siblings, which I treasure to this day.

How did you get involved with the Friends of Washington Crossing Park? What was it that led you to return to your roots, so to speak?

Around 2008, the State of Pennsylvania basically shut down the park because of a funding crunch, and the annual re-enactment of the Crossing was in jeopardy for the following year. The Friends group sent out a call for volunteers to help save the Crossing. My wife Bunkie and I were part of the crew that worked to make it happen; and, based on that success, the Friends decided to organize a group to keep the park open. After seeing a blurb in the newspaper, Bunkie and I attended a meeting and signed up to be tour guides at WCHP. After a year, we were hired as part of the FWCP staff and have been there ever since. As a history major who worked in sales in the corporate world, becoming a tour guide was an easy transition for me to make. I can think of nothing I would rather be doing than giving tours at the park.

I know you’re very interested in the concept of leadership and have given talks on Washington’s leadership style and particularly his decision-making in the context of the “Ten Crucial Days” campaign of 1776-1777? To what extent does your interest in this stem from your military and/or business experience and how so? Do you think Washington’s leadership offers us any lessons for today?

From my time in the military and my earliest days in the corporate world, I’ve been fascinated by the concept of leadership and curious about what it takes to be a successful leader. I wanted very much to be a platoon leader while in the Marines and was pleased to achieve that honor. Since then, I’ve been interested in learning how others became great leaders, and this led me to focus on George Washington.

Considering where GW came from and how he ended up, his is a truly remarkable story. That he and the ragtag group of citizen-soldiers he inherited hung together, grew by experience, and developed into an effective fighting force is nothing short of miraculous. What the hard corps of Washington’s men endured during their years of struggle is in large measure a tribute to the faith they placed in their leader. These soldiers were ill-clad, ill-fed, racked by disease, often unpaid, and faced with some of the most horrendous weather conditions imaginable.

I have come to admire Washington’s courage, commitment, and perseverance. Plus he was the ultimate team player; his collaborative style of decision-making allowed him to get a variety of input, which led to better decisions. I think his troops realized Washington would never give up. He believed deeply in the cause and simply refused to quit, no matter how difficult the circumstances his army faced. That passion trickled down to his men, and they believed in him.

As you can tell, I’m a huge GW fan. He was dedicated to doing what was best for the national interest, both in war and peace—something I don’t always see in our leadership today.

Other than a return to some semblance of normality in our current circumstances, is there anything in particular that you would like to see happen at WCHP as we go forward, either generally or specifically in connection with the upcoming observance of the 250th anniversary of American independence?

I feel strongly about using all of 2026 to focus on the 250th anniversary. Each month, WCHP should host a special event, like movies, speeches, book signings, and band concerts, among others, utilizing the auditorium in the visitor center. I would also like to see us make our July 4 celebration especially noteworthy that year—perhaps renting out the War Memorial Building in Trenton for a very special event that would include speeches by prominent guests. Let’s invite the President and the governors of New Jersey and Pennsylvania! I would love to see us plan this or another event jointly with the Old Barracks Museum and the Princeton Battlefield Society. We should prepare special children’s activities in observance of the 4th to go along with our usual park events, and finally I would suggest we update and expand our usual Crossing ceremony that December.

What has been your most memorable experience at WCHP?

During the Crossing ceremonies in 2010, I was given the FWCP Volunteer of the Year Award, which came as a complete surprise to me. Needless to say, I was very touched and most appreciative. What made it extra special was the fact that we were standing very close to the spot where I had lived for my first fifteen years. Truly a very memorable moment!

What gives you the most satisfaction of all the activities in which you’ve been involved at WCHP and why?

What I enjoy most is interacting with interested people who come to the park to learn more about the “Ten Crucial Days” of the Revolution. Many of our visitors do not have a good understanding of our early history, and I enjoy helping them learn more about this momentous period.

Thank you, Tom.

Final Thought

Although he turns 85 years young this year, Tom hasn’t gotten the memo about slowing down. During what has been an unsettling period for us all, it’s comforting to savor the timeless quality of certain things that so richly deserve our recognition and esteem. Washington Crossing Historic Park is one of those. Tom Maddock’s connection to it is another.