Reminder: If you’re reading this in your email, you have to click on the link at the bottom or go to dpauthor.com and click on the Speaking of Which tab in order to view the actual blog post with the featured image.

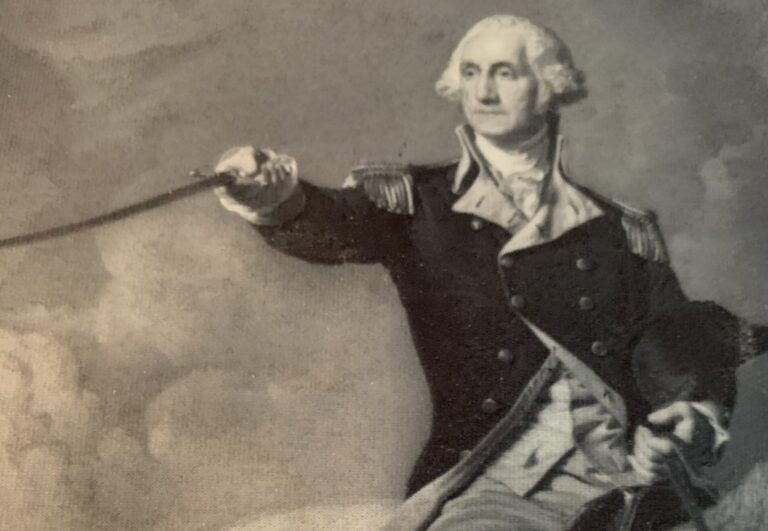

I’ve just had the pleasure of reading a chapter in a manuscript that the author asked me and others to review in connection with a book he’s crafting about what he considers to be the turning points of the war for independence, that is, the military events that altered the trajectory of the contest. This particular chapter covers the “Ten Crucial Days” (TCD) of the Revolution (December 25, 1776 – January 3, 1777), when George Washington’s army won its first three significant victories and profoundly reversed the momentum of the conflict. The draft cites to a quote by a noted military historian, the late Don Higginbotham, referring to the Continental Army’s legendary Christmas Night 1776 crossing of the Delaware River that began the TCD. Higginbotham asserted that this action was perhaps Washington’s “only really brilliant stroke of the war.”

Oh Yeah?

Having spent the last nine years immersed in the TCD, I certainly appreciate any recognition accorded any aspect of it by the historical community. That said, I would take issue with Professor Higginbotham’s assessment as being less than fair to GW, and that is the basis for what follows.

While perhaps not a brilliant strategist, Washington did have his moments . . .

(1) I don’t know if “brilliant” is the operative adjective for GW’s ordering Colonel Henry Knox to retrieve more than fifty cannon from Fort Ticonderoga in upper New York State in late 1775 and then placing them on Dorchester Heights outside British-occupied Boston, thereby forcing the British to evacuate the city in March 1776 or otherwise launch a suicidal attack, but I like to think it was an awfully shrewd piece of generalship. (And I’m not discounting that General William Howe, the British commander there, had been planning to leave Boston for months anyway or that GW’s generals had to dissuade him from launching imprudent attacks against the occupiers before then.)

(2) The evacuation of Washington’s army from Brooklyn Heights to Manhattan on the night of August 29-30, 1776 was one of the most skillful in military history, being executed at night in small craft on difficult water without detection by a larger and more powerful enemy army and fleet. (Yes, you could say it compensated—perhaps—for GW’s litany of errors in connection w/ the Battle of Long Island on Auguat 27, but still it saved his army from complete destruction. That moment was nothing if not pivotal.)

(3) The end run by GW’s army around General Charles Cornwallis’s left flank from Trenton to Princeton on the night of Jan. 2-3, 1777, which led to the final victory of the TCD at Princeton, was not exactly chopped liver.

(4) GW’s deployment of General Matthias Roche de Fermoy’s contingent along the route from Princeton to Trenton on New Year’s Eve 1777 proved to be absolutely brilliant thanks to the leadership of Colonel Edward Hand, whose delaying action on January 2, 1777 (in Fermoy’s absence) arguably forestalled the destruction of GW’s army at what I believe was the most pivotal military encounter of the war—the Battle of Assunpink Creek, which I define as including the skirmishing by Hand’s force and the fighting at the creek.

(5) If GW’s sending reinforcements from his own army (including Colonel Daniel Morgan’s riflemen) northward to support the resistance to General John Burgoyne’s Saratoga expedition in 1777 wasn’t brilliant, it sure as heck was very astute. Kevin Weddle makes a point of this in his recent book, The Compleat Victory: Saratoga and the American Revolution.

(6) To my way of thinking, GW’s naming General Nathanael Greene to command the Southern Department of the Continental Army in late 1780 was more than brilliant. It was genius. Greene’s masterful Southern campaign, in the face of seemingly insuperable challenges and with the vital assistance of rebel militia, drove the British from the interior of the Carolinas and pinned them inside their coastal sanctuaries in Charleston and Savannah, which they evacuated before the end of 1782.

(7) I’d have no hesitation in characterizing as “brilliant” the adroit maneuvers orchestrated by GW in the late summer of 1781 to deceive General Henry Clinton into thinking that a Franco-American assault on British-occupied New York City was impending in order to divert his attention from the movement of allied forces southward to trap Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, and thereby preclude Clinton’s timely intervention on behalf of Cornwallis in an attempt to forestall the climactic American military victory of the war.

(8) And while not of a strictly military nature, perhaps GW’s most brilliant stroke of the war was to order mass inoculation of the Continental Army against smallpox in 1777. (I suppose you could argue he had no choice, but it was still a dramatic gesture that was not without controversy and arguably indispensable to preserving the integrity of his army, as well as being the first major public health initiative ever undertaken in America.)

Oh well, history is an argument that never ends, by George.