Well, arguably that’s what this is about, a story of progress and ascension. Historian and author William L. (Larry) Kidder (seen above) has immersed himself in just such a tale over the last several months while working on his latest literary project. This will be Larry’s fifth book relating to the War of Independence. His other works include: Revolutionary Princeton 1774-1783: The Biography of an American Town in the Heart of a Civil War; Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds; Crossroads of the Revolution: Trenton, 1774-1783; and A People Harassed and Exhausted: The Story of a New Jersey Militia Regiment in the American Revolution.

Meet Larry Kidder

Born in California, Larry was raised there and in Indiana, New York, and New Jersey. He holds degrees in history from Allegheny College and is a US Navy veteran who served in Vietnam. Larry taught for forty years in public and private schools and for thirty years has been a volunteer historian, interpreter, and draft-horse teamster for Howell Living History Farm in Hopewell Township, NJ. His many pursuits as a public historian include his involvement with central New Jersey historical societies and active membership in: the Association for Living History, Farm, and Agricultural Museums; the Washington Crossing American Revolution Round Table; the New Jersey Living History Advisory Council; and the Advisory Council for Crossroads of the American Revolution.

Meet Jacob Francis

Larry’s upcoming book chronicles the complex and multifaceted story of the life of Jacob Francis, a free Black man, as he struggled with the systemic racism that accompanied enslavement during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It begins with his birth in 1754 to a free Black woman in Amwell Township, NJ, and takes him through his youth as an indentured servant, service in the Continental Army in 1775-1776, settling back in Amwell in 1777 and serving in the Hunterdon County militia, marrying and freeing an enslaved woman named Mary, establishing a farm, and raising a family in the area of Flemington, NJ. His youngest son carried on the fight for freedom in which Jacob engaged and became an abolitionist seeking not just the freedom of enslaved Black people but also their equal rights as citizens.

Q and A

Larry has been kind enough to share the following comments about his newest work. I am grateful to him for taking time from his congested schedule to delve into these matters here.

What motivated you to write at length about Jacob Francis?

When I first encountered Jacob’s story in his lengthy 1832 statement that listed his qualifications for a federal pension as a Revolutionary War veteran, he stood out as a man with exceptional skills and strength in surviving Continental Army service during the siege of Boston, the New York campaign, and finally the Battle of Trenton. He followed his fourteen-month Continental service in a Massachusetts regiment with extensive service in the New Jersey militia for the remainder of the war. I wanted to find out more about his life and to what degree he was able to avoid the all-too-common, white-racist expectation that he would achieve nothing better than a life as a poor laborer. Jacob obviously was concerned about equal rights for Black people in America as well as independence from Great Britain. He and his wife conveyed the importance of that struggle to their children.

I also wanted to investigate the story of a free Black man during the time of slavery since so much focus has rightfully been put on slavery. While an inhumane way of life for Blacks in America, enslavement was not the only means by which whites created systems to restrict Black lives, as the dehumanizing racist justifications for enslavement spilled over to foster a racist mindset throughout society against free Black people.

What about this story especially appealed to you, and how does it reflect the broader picture of life in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century America?

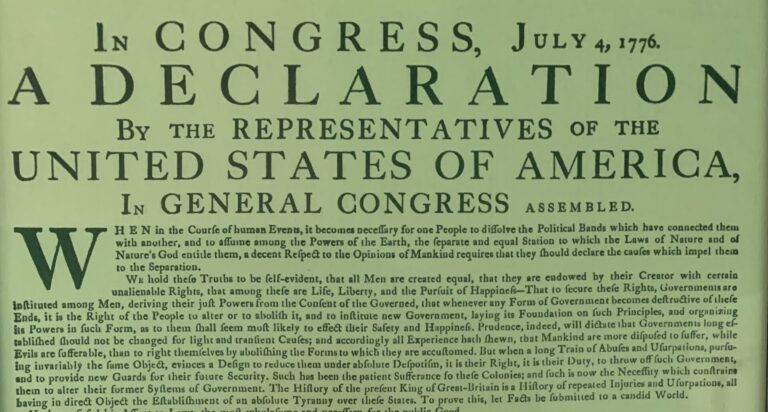

While much has been written about Black enslavement, investigating Jacob Francis offered the opportunity to look at the world inhabited by free Black people who were neither enslaved nor white yet were subject to obstacles deliberately put in place by whites to restrict their rights and opportunities for success in life. An examination of Jacob’s revolutionary world provided an opportunity to see further complexities in the culture of late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century New Jersey and to some degree other areas of the thirteen colonies that became states. He experienced at least two revolutions. What we normally think of as the American Revolution, which involved gaining independence from England and establishing a free government, was just one revolution. Jacob and his family also lived at a time when attitudes toward enslavement were changing and that was just part of an ongoing revolution involving the perception of Black people by white people. Since that revolution continues to this day, I wanted to see how today compares with Jacob’s time.

Part of your focus is on the abolition movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century and how it connected with Jacob’s life story. What did you learn about the movement that you might not have known before?

I already knew that during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was an inconsistent and evolving abolition movement and also a colonization movement aimed at returning freed Black people to Africa. What I came to realize more fully is that these movements were virtually one and the same in the beginning. Abolitionists were not fighting to free enslaved people so they could live among white people with equal rights. Rather, they were fighting to free enslaved people and then send them to Africa because they believed Black people would never be equal with whites in the United States and did not have the capacity to achieve equality. To change abolition into a civil rights movement, it took Black people like Jacob and Mary’s son, Abner, who worked to convince abolitionists to give up colonization and switch to helping Black people achieve equal rights.

What would you especially like readers to know about the institution of slavery as it impacted Jacob and the people in his life?

In many ways, Abner felt he was carrying on the fight for liberty that his father had waged in the Revolutionary War. Even though Jacob and his family, after he freed Mary, were already free, they still knew many enslaved people, and their “free” lives were directly affected by the racist laws and attitudes that supported slavery. While we still need to know more about the institution of slavery, how it operated, and how it affected peoples’ lives, we also need to know more about the lives of free Black people in the past to truly understand the systemic racism that lingers in a number of respects today. Just as current white-racist beliefs seek to distort human qualities in minorities even when they fly in the face of contrary evidence, so during Jacob’s time people like him daily demonstrated the falsity of such beliefs.

Do you think slavery affected the evolving policies of the Founders during the Revolutionary era?

In many ways, the Founders vehemently spoke about protecting their freedoms while ignoring that they were being hypocritical by enslaving people themselves. Some individuals did note this hypocrisy, and some Black men like Jacob who joined the Continental Army must have been fully aware of it.

What do people need to know about the role Blacks played in the Revolution?

It is important to know that Black men served with distinction in the military in a variety of ways throughout the war, even at times when high-ranking people like Washington wanted to exclude them. For example, Jacob enlisted practically on the same date that Washington ordered his officers not to enlist any Black men. In New England, Black men had served in military units for many years and were part of the armed force around Boston very early in the war. New Englanders were more likely than people in other areas to see the equal value in Black recruits with white ones. I think it is also interesting that even the leaders opposed to employing Black men in the army did permit it, especially when they could not find enough white men who were willing to join to fill the regiments. At least some Black recruits enlisted with the hope that their service would help dispel the stereotypical white-racist view of Black men as incompetent, immoral losers. Of course, some enslaved men found ways to join the army in the expectation that it would earn them freedom.

Is there anything else readers should bear in mind when they think about the realities of life for African Americans both before and after the Revolution?

It is very important to understand that the conditions of life in the thirteen colonies, and then states, for Black people were constrained, although in different ways, for those who were free as well as those enslaved. I also think it important to understand that similar constraints continue to exist today when laws are enacted that I believe make it difficult for minorities to engage in a full life equal with everyone else. And like today when there are many white people who actively support the idea of true equality for all, at the time of the Revolution and early Republic there were white people who sought to support minorities. Understanding the world of Jacob Francis can help us understand that our world today still features many similar problems. Although we no longer have slavery, the problems of minority citizens today have their roots in the conditions encountered by Jacob Francis and his family.

If Jacob had been a white man who left so little personal writing about his life and a historian undertook a biography that would place him in the context of time and place, there would have been some difficulties in fine- tuning his exact experiences. Because Jacob was Black, those difficulties are far greater due to the variables in how white people must have interacted with him and how rules and social customs would have applied to him. Those difficulties in researching and writing about him reinforce the importance of understanding the complexities he faced in life and that people in minority communities still face every day.

Thank you, Larry.

Final Thoughts

The story of Jacob Francis reflects the hardships and challenges faced by common people in early America, especially those with which Black people were forced to struggle in their efforts to secure freedom and elevate their condition. It is also a story of hope and inspiration that speaks to the aspirational character of American democracy in its ongoing effort to establish a more perfect Union, however gradual and often painful that endeavor has been. Larry Kidder’s latest literary effort will undoubtedly shed new light on this aspect of our national saga and the journey embedded within it that seeks to track the arc of the moral universe. As Dr. King reminded us, that curve is long but it bends toward justice.