Reminder: If you’re reading this in your email, you have to go to dpauthor.com and click on the Speaking of Which tab in order to view the actual blog post with the featured image.

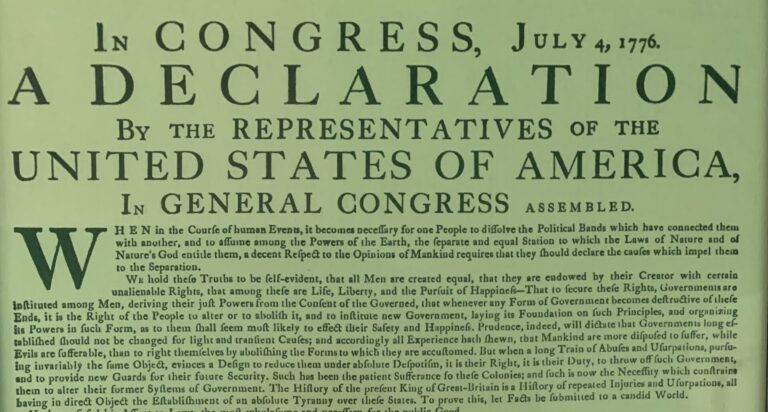

The following is from George Washington’s General Orders of July 9, 1776 to his troops announcing the Declaration of Independence, which were issued as the rebel army in New York City awaited an expected assault by the forces of the British crown gathering on Staten Island:

The Honorable the Continental Congress, impelled by the dictates of duty, policy and necessity, having been pleased to dissolve the connection which subsisted between this Country, and Great Britain, and to declare the United Colonies of North America, free and independent STATES: The several brigades are to be drawn up this evening on their respective Parades, at six OClock, when the Declaration of Congress, shewing the grounds & reasons of this measure, is to be read with an audible voice.

The General hopes this important Event will serve as an incentive to every officer, and soldier, to act with Fidelity and Courage, as knowing that now the peace and safety of his Country depends (under God) solely on the success of our arms: And that he is now in the service of a State, possessed of sufficient power to reward his merit, and advance him to the highest Honors of a free Country…

On that same day in New York City, a mob, inspired by Congress’s declaration, toppled the equestrian statue of King George III on Bowling Green. Its lead contents would be repurposed, according to Lieutenant Isaac Bangs of Massachusetts, “to be run up into Musquet Balls for the use of the Yankies.” The fact that the unruly crowd utilized a number of enslaved persons to dismantle the statue—acting in the cause of the colonists’ cherished liberty against a detested symbol of the English monarchy—vividly illustrates the stark contradiction that existed between their revolution in support of self-determination and the chattel slavery that constituted America’s most iniquitous institution.

On July 6, Colonel John Haslet of the Delaware Continental Regiment wrote his friend and political ally Caesar Rodney, a member of Congress who had voted for independence, to offer his endorsement of the Revolutionary edict: “I congratulate you, Sir, on the Important Day, which restores to Every American his Birthright—a day which Every Freeman will record with Gratitude, & the Millions of Posterity read with Rapture.”

Not surprisingly, Ambrose Serle had a somewhat different take on this congressional action. Writing in his journal on July 13, the private secretary to Admiral Richard, Lord Howe—who would command His Majesty’s fleet in the impending 1776 New York campaign—opined as follows:

The Congress have at length thought it convenient to throw off the Mask. Their Declaration of the 4th of July, while it avows their Right to Independence, is founded upon such Reasons only, as prove that Independence to have been their Object from the Beginning. A more impudent, false and atrocious Proclamation was never fabricated by the Hands of Man. Hitherto, they had thrown all the Blame and Insult upon the Parliament and ministry: Now, they have the Audacity to calumniate the King and People of Great Britain. ‘Tis impossible to read this Paper, without Horror at the daring Hypocrisy of these Men, who call GOD to witness the uprightness of their Proceedings, nor without Indignation at the low and scurrilous Pretences by wch they attempt to justify themselves. Surely, Providence will honor its own Truth and Justice upon this Occasion, and, as they have made an appeal to it for Success, reward them after their own Deservings.

Gee, I sure wish he didn’t sugarcoat it like that. I want to know what he really thought.

Best wishes for an enjoyable Fourth.