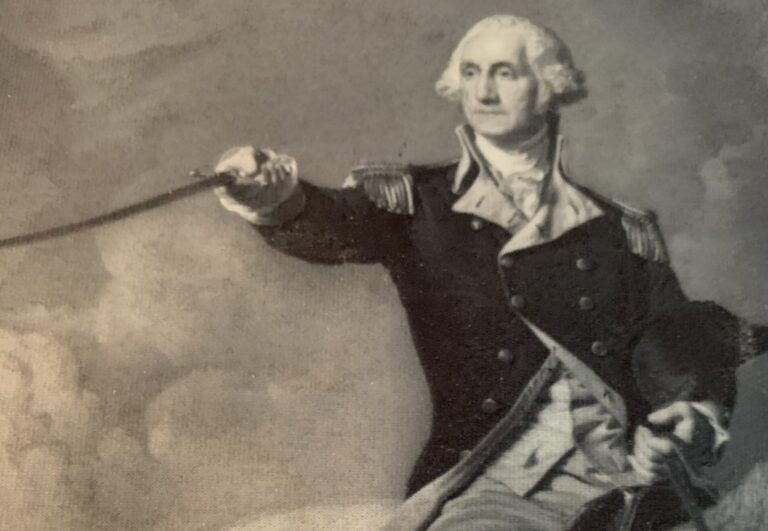

As we approach the 246th anniversary of the Battle of Harlem Heights (depicted above in a nineteenth-century print by James Charles Armytage), a few words are in order about an unsung hero who made the ultimate sacrifice in the cause of American independence that day. (This post is adapted from The Battle of Harlem Heights, 1776, soon to be released by Westholme Publishing.)

Who Was He?

Andrew Leitch was a twenty-eight-year-old Scottish-born merchant and resident of Dumfries, Virginia, who had moved from Maryland in 1774. He hosted George Washington at his home in March 1775 while serving as a member of the Prince William County committee of correspondence and visited Mount Vernon a month later. Leitch left his wife and children to join the Continental Army, was commissioned as a captain in the 3rd Virginia Regiment in February 1776 and then as a major in the 1st Virginia. He marched to New York with the 3rd Virginia, as they were a few weeks ahead of the 1st Virginia, but did not join up with Washington’s army until early September. The 3rd Virginia was a favorite of Washington’s, as he was familiar with many of its officers from the Fredericksburg area.

What Did He Do?

On September 16, 1776, Leitch was assigned to a party of about 230 men commanded by Colonel Thomas Knowlton of Connecticut, which comprised Knowlton’s Rangers (the army’s first intelligence and reconnaissance unit) and three companies of riflemen from the 3rd Virginia. They were ordered by Washington to execute a flanking maneuver against the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of General Alexander Leslie’s light infantry and the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot, known as “The Black Watch.” Leitch led the Virginia contingent that accompanied the Rangers in this effort.

At about eleven a.m., Knowlton’s force set out from Point of Rocks (at today’s 127th Street and Nicholas Avenue in upper Manhattan), far east of the fighting between the American front lines and Leslie’s units, to begin its encircling maneuver. Proceeding as unobtrusively as possible, the Rangers and Virginians crossed the Hollow Way, a valley that separated the opposing forces, and headed for a rocky rise in an area now encompassed by 123rd and 124th Streets, Broadway, and Amsterdam Avenue, from where they intended to advance south and west to move into position behind the light infantry and seal the trap shut.

Meanwhile, the American troops in front of Leslie’s light infantry enjoyed an advantage in firepower that forced the outnumbered redcoats to pull back after standing their ground for nearly an hour, and the British retreat may have occurred before the flanking movement could get in their rear. Traditional accounts suggest that an errant order to fire foiled the American attempt to envelop the light infantry, according to which the culprit was an unidentified officer in the 3rd Virginia who inexplicably gave the command before the flankers could get behind the enemy—whereupon Knowlton’s force began shooting and the British reciprocated. In any case, the planned assault on the British rear was now directed at the right side of their formation instead, as the chance to surround them evaporated.

The exchange of fire between Leslie’s men and the flankers began just as Leitch, positioned at the front of the rebel contingent, reached the top of a ledge on the rocky rise from which they intended to swing southwest behind the enemy. He was struck three times in short order and carried to the rear. “He conducted himself on this occasion in a manner that does him the greatest Honor and so did all his Party,” wrote Colonel David Griffiths of Maryland, “till he received two balls in his belly and one in his hip.” Mounting the same ledge where Leitch had fallen, Knowlton turned to urge his men to follow him and almost immediately was hit from behind by a British musket ball, sustaining a mortal wound. Both officers fell while exhorting their troops to stand up to the world’s finest infantry, and those men continued to trade fire with the light infantry. This was quite possibly the pivotal moment in the battle, when the fall of Leitch and Knowlton might have so dispirited their men as to enfeeble their attack. That they stood their ground is a tribute to the resolve and competence of the officers and men in the detachment. Perhaps they fought all the harder to avenge the loss of their commanding officers, and their stubborn resistance contributed to the army’s first battlefield success.

In his congratulatory order to the army the next day, Washington wrote: “The General most heartily thanks the Troops commanded yesterday by Major Leitch, who first advanced on the Enemy and the others who so resolutely supported them.” Leitch was removed to the Blue Bell Tavern and clung to life there for another two weeks, breathing his last on October 1 or 2.

Afterwards

Fourteen years later, Leitch’s daughter Sarah wrote to President Washington, noting that her father “actuated by Zeal in the cause of this Country entered into the Army of these States, and in the year 1776 Sacrificed his Life in executing the orders of his General.” On behalf of herself and her brother James, who had lost their mother shortly after Andrew’s death, Sarah did “humbly intreat therefore that the half pay of the Commission possessed by their said Father, may be extended to your Petitioners commencing from the date of his Death, or for such other provision as you may think most proper.” Her petition was laid before Congress on January 25, 1791 and referred to Secretary of War Henry Knox, who reported on February 15, 1791 in favor of granting the request. The House of Representatives resolved to grant the petition on February 26, but it is unclear whether the resolution was acted upon. On June 30, 1834, Congress resolved to pay “to the legal representatives of the late Margaret Leitch, widow of the late Major Andrew Leitch, a major in the army of the revolution…the seven years’ half pay” to which “widows and children were entitled by the resolution of Congress of the twenty-fourth of August seventeen hundred and eighty.”