April 17 marks the 231st anniversary of Benjamin Franklin’s passing; and, well, there isn’t much he didn’t do during his eighty-four years. The man who demonstrated that lighting is electricity by flying a kite—one of the most significant (ahem) current events of his time—and invented a rod to control its force was himself an extraordinary force in the social, economic, and political life of eighteenth-century America. He became, according to Walter Isaacson (in Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, Simon & Schuster, 2003), “America’s best scientist, inventor, diplomat, writer, and business strategist, and . . . also one of its most practical, though not most profound, political thinkers.” But I want to focus here on his role in helping win American independence from Great Britain, the mother country he so admired until its colonial policies alienated Franklin and finally drove him to support a permanent separation from the British Empire.

The Aging Revolutionist

The oldest of our Founding Fathers—he was seventy when the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress in which he served—was also the most approachable, more man than myth in contrast to the likes of George Washington and other framers. If indeed Franklin “winks at us” in Isaacson’s imaginative turn of phrase, this suggests a charm and congeniality that would lend itself to an easy familiarity with posterity. Yet most people today have little if any understanding of how vital a part Franklin played in America’s struggle for the right to rule itself. He deserves a greater appreciation in our collective historical consciousness for his efforts on behalf of America’s Revolutionary enterprise.

America’s Representative to the World

The world’s most famous American arrived in France in late 1776, having been chosen by a congressional committee, with his objective being to beguile the court of King Louis XVI into proffering the assistance and alliance that young America desperately needed to fend off France’s archenemy, England, Although he was joined by two other congressionally selected commissioners, Silas Deane of Connecticut and Arthur Lee of Virginia, Franklin enjoyed a singular status among the Parisians, who esteemed him above all other Americans. For more than eight years, the celebrated philosopher-statesman, who symbolized to his many Old World admirers both a righteous frontier freedom and an Enlightenment intellect, carried out his mission with aplomb. Isaacson writes that Franklin employed “a clever and deliberate manner, leavened by the wit and joie de vivre the French so adored, [to] cast the American cause, through his own personification of it, as that of the natural state fighting the corrupted one, the enlightened state fighting the irrational old order.”

Franklin held in his ambassadorial hands, as much as did Washington or any other advocate of American independence, the fate of his country’s contest with Britain. For without French aid, recognition, and naval support, America’s chances of success were marginal. Isaacson asserts that Franklin—already the greatest America scientist and writer of his time—displayed “a dexterity that would make him the greatest American diplomat of all times. He played to the romance as well as the reason that entranced France’s philosophes, to the fascination with America’s freedom that captivated its public, and to the cold calculation of national interest that moved its ministers.”

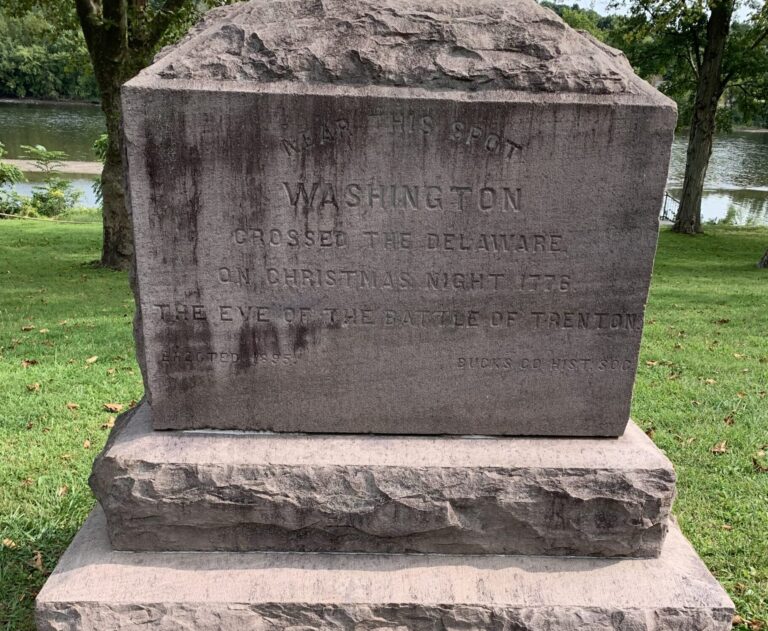

In February 1778, encouraged by the decisive Patriot victory over General Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga the previous October, France entered into a formal alliance with the United States. A global conflict ensued in which France, Spain, and the Netherlands opposed Britain and thereby drained resources from the latter’s campaign to subdue the American rebellion. French troops, naval prowess, and tactical expertise were absolutely indispensable to ensuring the climactic defeat of Lord Cornwallis’s besieged force at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781.

Summing Up

Franklin’s contribution to the cause of American independence, while largely underrated in the public’s imagination, was monumental. His deft diplomacy proved instrumental in securing an alliance with a powerful ally without whose assistance our rebellion would likely have foundered.

This New World original represented a formidable asset to the Revolutionary endeavor, whether it was helping to craft the Declaration of Independence, skillfully advocating for a new nation’s interests as its leading statesman in Paris, or playing a key role in negotiating the treaty by which Britain officially acknowledged the new American nation in 1783. As his friend and Louis XVI’s finance minister, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, famously wrote of this most enterprising Patriot, “He snatched lightning from the sky and the scepter from tyrants.”

Perhaps Franklin’s triumph as a diplomat should have been no surprise given how successful he was in so many other pursuits throughout a long and accomplished life. The man’s extraordinary range of interests and talents translated intro a remarkable record of achievement in business, science, civic affairs, authorship, and statecraft.

And not to be disparaging, but anyone who says otherwise can (you knew this was coming) go fly a kite.