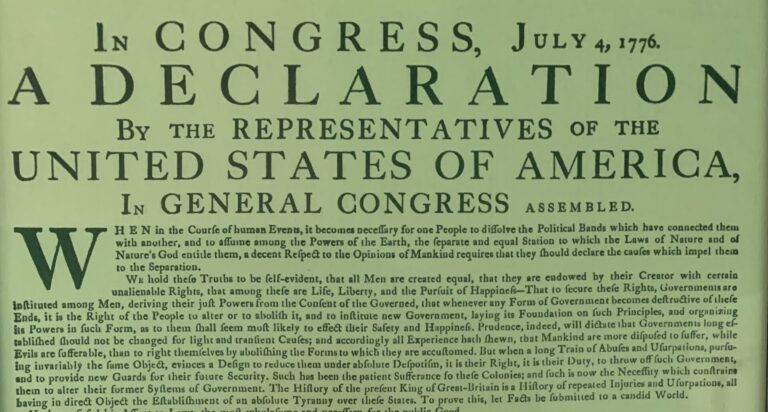

John Adams and his fellow delegates to the Continental Congress voted for independence from Great Britain on July 2, 1776. Two days later, they adopted the precise language setting forth their assertion of national sovereignty by approving the Declaration of Independence.

Up and Adams

Perhaps no one has conveyed the drama and passion of America’s birth more eloquently than Adams did when writing to his wife Abigail from Philadelphia between the congressional actions of July 2 and 4.

The following are selected excerpts from that letter:

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony “that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do.” You will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell’d Us to this mighty Revolution, and the Reasons which will justify it. in the sight of God and Man. . . .

Time has been given for the whole People, maturely to consider the great Question of Independence and to ripen their Judgments, dissipate their Fears, and allure their Hopes, by discussing it in News Papers and Pamphlets, by debating it, in Assemblies, Conventions, Committees of Safety and Inspection, in Town and County Meetings, as well as in private Conversations, so that the whole People in every Colony of the 13, have now adopted it, as their own Act. . . .

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the history of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

A voice of less renown but no less conviction, that of Colonel John Haslet of the Delaware Continental Regiment, weighed in on the significance of the delegates’ action in Philadelphia in a letter to his friend and Adams’s fellow congressman, Caesar Rodney, on July 6. Haslet, a former Presbyterian minister who had served in Delaware’s colonial assembly prior to donning a uniform and would become a martyr to the cause of independence just six months later, penned the following: “I congratulate you, Sir, on the Important Day, which restores to Every American his Birthright—a day which Every Freeman will record with Gratitude, & the millions of Posterity read with Rapture.”

And Now?

The Founding Fathers—particularly the slave owners who constituted at least a third of those signing the Declaration of Independence—launched a struggle to achieve liberty and independence for some but not all their fellow Americans. Most of these Patriots beheld a vision of freedom and equality that did not extend to those in bondage and was severely restricted for women, Indians, and men without property.

Since then, our vision of American democracy has expanded to become a decidedly more inclusive one, its application being gradual and sometimes painful in a process marked by both ballots and bullets. We’ve seen the Nation’s governance evolve into what our sixteenth president, on a long-ago Independence Day, termed “that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is, to elevate the condition of men—to lift artificial wights from all shoulders—to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all—to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life” (Abraham Lincoln, Message to Congress in Special Session, July 4, 1861). It is the framework—with all its flaws and limitations—of which a British prime minister once spoke in addressing the House of Commons: “Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time” (Winston Churchill, November 11, 1947).

Ultimately, of course, our governance is rooted in how we perceive ourselves. An observation that lays claim to earnest contemplation, from political philosopher Steven B. Smith, speaks to what is unique about American patriotism: “It is not based on European beliefs about ‘blood and soil,’ or biblical beliefs about attachment to the land, but from the beginning has contained a deliberative and self-questioning character. American patriotism is not only a statement of who we are, but also an aspiration to what we might become. To be an American is to be continually engaged in asking what it means to be an American” (Reclaiming Patriotism in an Age of Extremes, Yale University Press, 2021).

Ready. Aim. Aspire.

And may the Fourth be with you.