Please Note: The images of a brutish and needless conflict instigated without provocation and orchestrated by a murderous and delusional bully, which have splashed across our screens the last few days, made me somewhat hesitant to publish a blog post about any type of military engagement at this point, even though I realize one has nothing to do with the other—except perhaps to remind us yet again that, as General William T. Sherman once observed, “War is cruelty and you cannot refine it.” And more so today than ever before.

But notwithstanding all that, here goes . . .

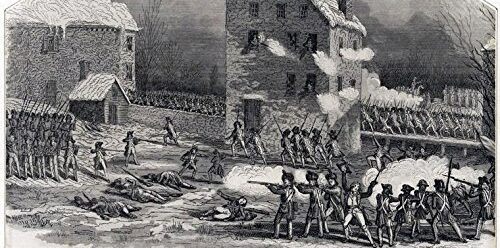

The Battle of Assunpink Creek, also known as the Second Battle of Trenton, on January 2, 1777 (imaginatively depicted in the nineteenth-century print above) was the second of three military engagements during the Continental Army’s triumphant winter campaign from December 25, 1776 through January 3, 1777—what historians commonly refer to as the “Ten Crucial Days.” (For the Patriot cause, these might also be termed the “Tense Crucial Days.”) The desire to correct its neglect in our collective historical memory was the genesis of my second book, The Road to Assunpink Creek: Liberty’s Desperate Hour and the Ten Crucial Days of the American Revolution. I contended there and have since that this affair—largely ignored by historians until David Hackett Fischer’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning Washington’s Crossing (Oxford, 2004)—was arguably the most pivotal military engagement of the war for independence.

Why Did it Matter?

Traditional accounts of this period in the Revolutionary War have treated the clash at Assunpink Creek as the “Rodney Dangerfield” of military encounters, emphasizing instead the first battle at Trenton on December 26, 1776, in which Washington’s army overcame the Hessian brigade occupying the town after the legendary Christmas night crossing of the Delaware River, and the battle at Princeton on January 3, 1777 that provided the Continentals with the capstone victory of their winter offensive (very offensive if you were British).

But consider this . . .

— Had Washington been defeated at Assunpink Creek, his victory at Trenton on December 26 would have been a historical footnote that did nothing to alter the strategic dynamic of the contest and there would have been no victory at Princeton on January 3 because in all likelihood there would have been no American Army to march there.

— The second battle involved the largest number of soldiers of the three engagements fought during the 1776-1777 winter campaign, particularly if one includes both the fighting between the Anglo-German army as it approached Trenton and the skirmishers under Colonel Edward Hand resisting its advance and the follow-up confrontation when the Crown’s forces attempted to cross the Trenton bridge spanning the creek.

— If we compare the three battles, this was the only one in which the enemy had a numerical advantage. It was also the only one in which Washington’s army fought both British and Hessian troops, and in which the enemy forces were led by a British general (Charles Lord Cornwallis, probably the most competent and energetic field commander in the King’s army). Moreover, it was the only one in which the geographic position of the American troops was such that they were in danger of being trapped between two waterways—the creek in their front and the Delaware River at their back—with no means of escape if they were outflanked and pushed up against the river.

— This was the longest battle of the “Ten Crucial Days” if one counts as a single encounter the resistance offered by Colonel Hand’s contingent during their fighting withdrawal from Maidenhead (Lawrence Township today) to Trenton and the clash at the creek immediately following the delaying action.

— January 2, 1777 was the first time the Continental Army repulsed an attack by British troops during a truly significant battle. Had the rebel army failed to stop their adversary’s advance at Assunpink Creek, the result would probably have been the destruction of that army and possibly the cause of American independence. And in that scenario, Washington would most likely have met his end on the battlefield or suspended from a British rope.

— The recollections of those present attest to the gravity of this moment: Major James Wilkinson—“If there ever was a crisis in the affairs of the Revolution, this was the moment”; Ensign Robert Beale of Virginia—“This was the most awful crisis”; Captain Stephen Olney of Rhode Island—“It appeared to me then that our army was in the most desperate situation I had ever known it”; and Private John Howland of Rhode Island—“Had the army of Cornwallis…crossed the bridge, or forded the creek, unless a miracle intervened, there would have been an end of the American army.”

— In Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (Viking, 2016), Nathaniel Philbrick opines that if Cornwallis’s effort to cross the Trenton bridge and overrun the rebel army had succeeded, “the war was as good as finished” for the capital city of Philadelphia “would surely [have fallen] that winter, and the Continental Congress in Baltimore might very well [have decided] that a negotiated settlement was in the country’s best interests.” Washington’s decision to fight here, he writes, created “the make-or-break moment” of the Revolutionary struggle.

Bottom Line

I’ll rest my case with the following excerpt from The Road to Assunpink Creek (the author says it better than I can):

Historians of the Revolution never mention Assunpink Creek in the same breath as Saratoga or Yorktown—the most recognized and significant battles in that struggle, with the former in 1777 leading to France’s crucial intervention in the contest and the latter in 1781 breaking the back of England’s will to fight against the colonials—but those later engagements might very well have never occurred if January 2, 1777 had turned out differently for Washington’s army. The events of that day, including the delaying action by Colonel Hand’s men and the fighting at the creek, plausibly created a deciding moment of as great consequence for the cause of American independence as the far better-known confrontations that occurred later in the war. Perhaps no military action in our country’s history is more paradoxical than the one on the road to Assunpink Creek, and at the bridge that crossed it, in the sense that its obscurity in the public mind and neglect by many historians is so disproportionate to its impact on the course of a conflict with global implications.

In other words, if things had gone differently that day, the quest for American independence may very well have been (ahem) up the creek.