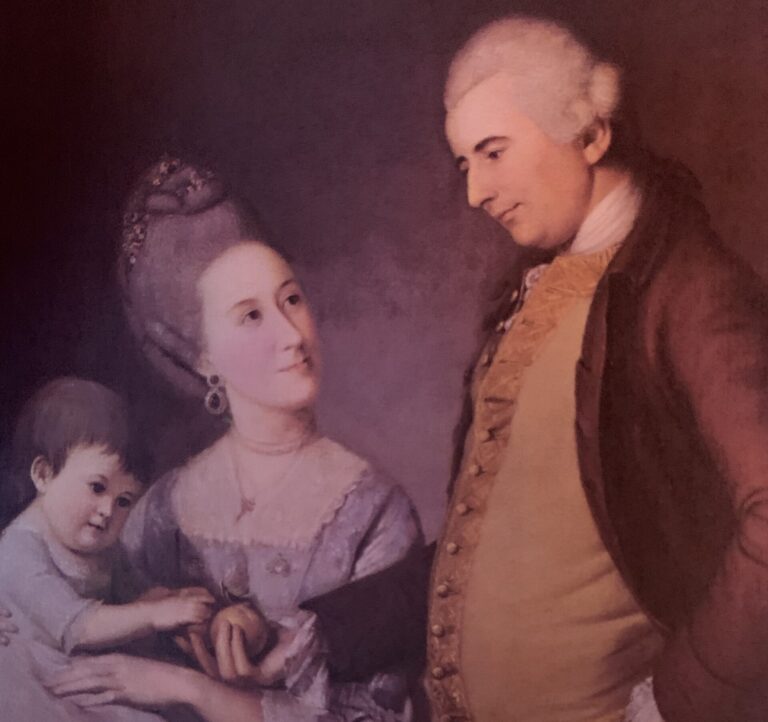

The above image of John Cadwalader and his wife Anne and eldest daughter Elizabeth was painted in 1772 by one of the most noteworthy artists of that era, Charles Willson Peale. According to one writer, Cadwalader was “respected as a man of energy, of strong convictions, and of the highest integrity.” (Nicholas B. Wainwright, Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964) Washington described him as “a military genius, of a decisive and independent spirit, properly impressed with the necessity of order and discipline and of sufficient vigor to enforce it.” (John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 1932, Vol. 37, 548)

A Privileged Revolutionary

In 1776, Cadwalader was a thirty-four-year-old merchant and prominent member of the Philadelphia gentry who had served on the city’s Committee of Safety and risen to command the volunteer militia known as the Philadelphia Associators, first organized in 1747 by Benjamin Franklin and then mustered anew in 1776. The Associators represented a cross-section of the population in Philadelphia—then the largest city in America with some forty thousand inhabitants—as well as volunteers from rural Pennsylvania counties, and among their officers was the artist Peale.

Cadwalader was taken prisoner when Fort Washington fell to General William Howe’s British and Hessian army on November 16, 1776 but was immediately released in consideration of favorable treatment received by a British prisoner at the hands of the colonel’s father in Philadelphia. He led over a thousand men of the Philadelphia Associators when they joined up with the Continental Army in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in December 1776, although these troops brought no actual combat experience with them. They were supposed to cross the Delaware River from Bristol on Christmas night to support Washington’s attack against the Hessian brigade in Trenton, but were stymied in their efforts to do so by the buildup of ice on the river that was more severe in the area below where the main rebel force crossed. However, Cadwalader’s men urged him to undertake an unplanned crossing on December 27 and thereby created the catalyst for a critical sequence of events, without which Cadwalader inferred that the raid on the Hessians at Trenton would have limited significance.

A Key Role in the “Ten Crucial Days” Campaign

Washington’s troops had returned to Pennsylvania after their raid on Trenton, but the deliberations of the commander-in-chief and his generals at their December 27 council of war were informed by the knowledge that Cadwalader’s 1,500 men—comprising about 1,100 Philadelphia Associators and a brigade of about 350 New England Continentals under Colonel Daniel Hitchcock of Rhode Island—had crossed the river to New Jersey that morning in its second attempt to do so. The colonel reported this unexpected development in a dispatch that arrived at army headquarters just before the council of war convened, in which he advised that the enemy was fleeing in panic and that the way was open to drive them from the western half of New Jersey. With Cadwalader’s dispatch in hand, Washington realized he had a golden opportunity to follow-up the attack on December 26 with a broader offensive that could change the whole dynamic of the contest. Orders were issued for the army to cross the river back to New Jersey, which it did over the next three days.

Once Washington returned to Trenton, he received intelligence from Cadwalader about the disposition of British troops in Princeton. The latter had met with a “very intelligent young gentleman” who was detained overnight by the redcoats but released on the morning of December 30. This youthful Patriot, whose identity is unknown, informed Cadwalader of the buildup of enemy troops and described in great detail how they were positioned. Based on this report, Cadwalader drew a crude map of the town indicating the strengths and weaknesses of the British alignment. From this sketch, Washington discerned an opportunity to make a successful move against his adversary. The British in Princeton were establishing strong defenses that included artillery and breastworks to guard against a possible American incursion from the north, west, or south. But they had neglected to fortify the eastern side of the town, which lay open to attack. Cadwalader’s map included a route from Trenton by which Washington’s army could approach Princeton from the east, where the enemy was most vulnerable.

Armed with this information, Washington held another council of war on the evening of January 1. He and his officers needed to consider how to respond to the large enemy force gathering in Princeton. It was decided to bring Cadwalader’s contingent from its encampment at Crosswicks to Trenton in order to strengthen the army’s position in the coming battle. Cadwalader’s militia reinforced the Continental regulars when the British attacked at the Second Battle of Trenton (or the Battle of Assunpink Creek) on January 2, 1777. The Americans held off the enemy and that night marched to Princeton under the cover of darkness, where they won the capstone victory of their pivotal “Ten Crucial Days” campaign the next day. Cadwalader’s brigade assisted in the final attack that drove the heavily outnumbered British from the field.

Afterwards

The colonel of the Philadelphia Associators was appointed brigadier general of the Pennsylvania militia in 1777 but declined Continental Army appointments to brigadier general and to brigadier and commander of the cavalry. In 1778, he left military service and returned to his family’s estate in Shrewsbury, Maryland. That year, he fought a duel with Washington’s nemesis, Thomas Conway, over the latter’s alleged “cabal” among certain army officers against Washington’s leadership, inflicting a nonfatal wound on Conway. After the war, Cadwalader moved from Pennsylvania to Maryland and served in its House of Delegates. He died in Shrewsbury at age forty-four in 1786.

Want More?

If you’re interested, you can dig deeper into Cadwalader by way of two recent articles in the Journal of the American Revolution:

John Cadwalader, Twice Refuses to be a General, September 13, 2022, by Jeff Dacus

The Significance of John Cadwalader, September 22, 2022, by yours truly

Dear Subscriber:

You’ve just read post number 50 in the Speaking of Which blog that was launched in August 2020, and I hope you’ve enjoyed them. If so, perhaps you’d consider sharing your thoughts about this series for others to consider by emailing a sentence or two to yours truly at [email protected]. I’m grateful to those of you who’ve already done so—and if you’re uncertain whether you fall into that category or wish to know what others have said, you can check under Comments on David’s Blog on the Contact page of this website. (You’ll notice these are written in the third person.)

Many thanks for reading!!

Best regards,

dp