Who Fought

Next Tuesday marks the 239th anniversary of one of the more obscure military encounters in young America’s quest for independence, and one of its bloodiest—at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, on September 8, 1781. Although this was the last major battle in the Southern theater of the Revolutionary War, it has been eclipsed in historical memory by the climactic military event of the conflict one month later. The surrender of Lord Charles Cornwallis’s beleaguered garrison at Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19 to a Franco-American army commanded by George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau overshadowed the struggle in South Carolina.

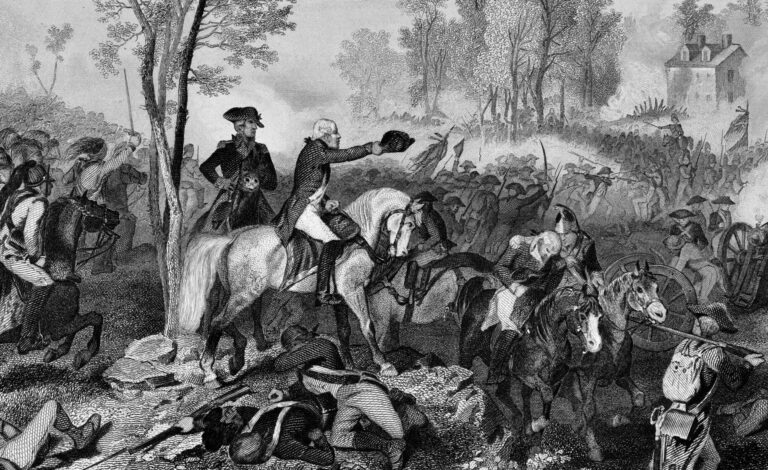

Eutaw Springs Battleground Park is near today’s Eutawville, some fifty miles northwest of Charleston—then occupied by the British. Here some 2,400 Americans led by General Nathanael Greene, half of them Continental soldiers and the rest militia, collided with 2,000 British regulars and Loyalists under Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart. The combatants were bathed in blistering heat during a four-hour engagement, one of the longest of the war, and over 1,200 were killed, wounded, captured, or missing—including more than a third of Stewart’s army and at least twenty percent of Greene’s.

Who Won

Both sides claimed victory. For the British, the outcome was arguably a tactical win because they held the field but a strategic setback. It sliced deeply into their limited troop presence in the Carolinas and failed to neutralize Greene’s army or rally public support for the royal cause. The same could be said of Greene’s clashes with the King’s forces at Guilford Courthouse and Hobkirk’s Hill earlier that year.

Colonel Otho Holland Williams of Maryland, who commanded a brigade in the battle, characterized it as a “steady and desperate conflict.” He argued that the “evidence [of victory] is altogether on the American side” as it regrouped after evacuating the field and set off in pursuit of the enemy army. The latter “relinquished the country it commanded” and withdrew to Charleston.

What It Meant

The civil war then raging between Loyalists and Whigs in the South continued into the following year, but the rebels controlled the countryside after the slugfest at Eutaw Springs. The British troops occupying Charleston and Savannah no longer ventured inland and would evacuate both seaports by the end of 1782.

Even before this battle, Nathanael Greene had described his troops’ combat experience during their remarkable Southern campaign in one famously memorable sentence. Reflecting on his success in wearing down their adversary by making British victories so costly while preserving the integrity of his army, the wily general wrote: “We fight, get beat, rise and fight again.”

In his second volume of Poems Written and Published During the American Revolutionary War, Philip Freneau memorialized the Americans who fell on that September day. His elegy, “At Eutaw Springs the Valiant Died,” ends with this verse: “Now Rest In Peace, our patriot band; Though far from nature’s limits thrown, We trust they find a happier land, A brighter sunshine of their own.”