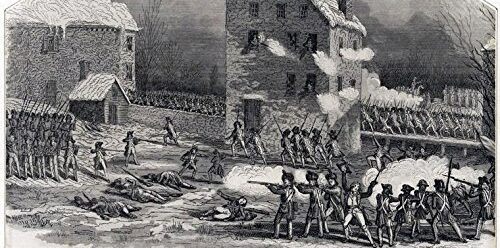

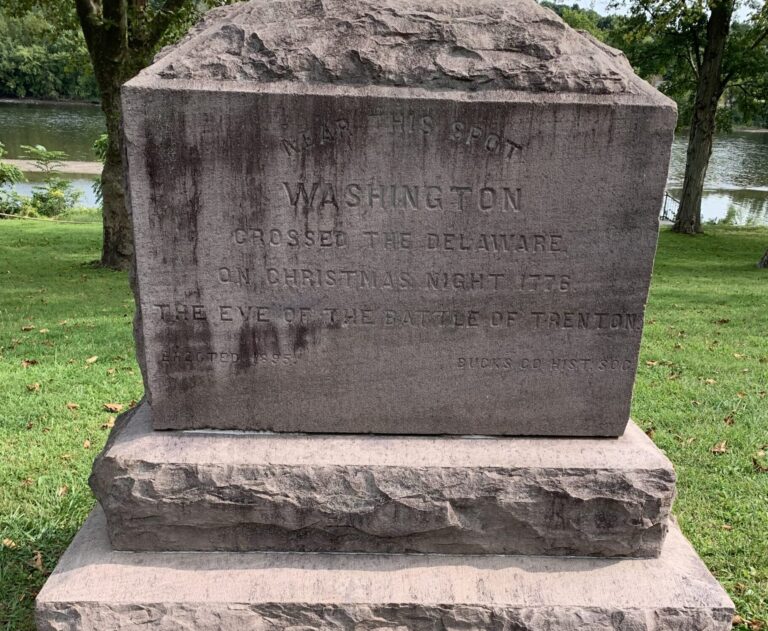

Rev War buffs are about to commemorate the 245th anniversary of the “Ten Crucial Days” campaign—from December 25, 1776 through January 3, 1777, perhaps the ten most remarkable days in American history—that reversed the momentum of the war for independence just when the Revolutionary enterprise seemed on the verge of final defeat, The battles at Trenton and Princeton—the first significant victories for Washington’s army—altered not only the course of the conflict but the public image of the Continental Army’s commander-in-chief as well.

In this season of remembrance, I thought it timely to recall some observations about these events here:

SIR GEORGE OTTO TREVELYAN, British Historian—It may be doubted whether so small a number of men ever employed so short a space of time with greater and more lasting effects upon the history of the world. (Source: The American Revolution in six volumes, Sir George Otto Trevelyan, 1899-1907)

FREDERICK II, King of Prussia, 1740-1786 (Frederick the Great)—The achievements of Washington and his little band of compatriots between the 25th of December and the 4th of January, a space of ten days, were the most brilliant of any recorded in the annals of military achievements. (Source: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, William S. Stryker, 1898)

THOMAS PAINE, Author and pamphleteer—The conquest of the Hessians at Trenton by the remains of a retreating army…is an instance of heroic perseverance very seldom to be met with. And the victory over the British troops at Princeton, by a harrassed and wearied party, who had been engaged the day before and marched all night without refreshment, is attended with such a scene of circumstances and superiority of Generalship, as will ever give it a place on the first line in the history of great actions. (Source: The American Crisis, Number V, Thomas Paine, March 21, 1778, in Thomas Paine, Collected Writings, 1955)

JAMES WILKINSON, Major, Continental Army—The joy diffused throughout the union by the successful attack against Trenton, reanimated the timid friends of the revolution, and invigorated the confidence of the resolute. Perils and sufferings still in prospect, were considered the price of independence, and every faithful citizen was willing to make the sacrifice. Success had triumphed over despondency, and the heedless, headlong enthusiasm, which led the colonists to arms, had settled down into a sober sense of their condition, and a deliberate resolution to maintain the contest at every hazard, and under every privation. (Source: Memoirs of My Own Times, James Wilkinson, 1816)

MERCY OTIS WARREN, American poet, dramatist, and historian—Perhaps there are no people on earth, in whom a spirit of enthusiastic zeal is so readily enkindled, and burns so remarkably conspicuous, as among the Americans….The energetic operation of this sanguine temper, was never more remarkably exhibited, than in the change instantaneously wrought in the minds of men, by the capture of Trenton at so unexpected a moment. (Source: History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, Mercy Otis Warren, 1805)

ALEXANDER HAMILTON, Captain, Continental Army—After escaping the grasp of a disciplined and victorious enemy, this little band of patriots were seen skillfully avoiding an engagement until they could contend with advantage and then by the masterly enterprises of Trenton and Princeton, cutting them up in detachments, rallying the scattered energies of the country, infusing terror into the breasts of their invaders and changing the whole tide and fortunes of the war. (Source: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, William S. Stryker, 1898)

LORD GEORGE GERMAIN, British Secretary of State for North America—All our hopes were blasted by that unhappy affair at Trenton. (Source: Remarks by George Germain, May 3, 1779, in The Parliamentary Register: Or History of the Proceedings and Debates of the House of Commons during the Fifth Session of the Fourteenth Parliament of Great Britain, Volume XI, John Stockdale, 1802)

HENRY KNOX, Brigadier General, Continental Army—I look up to heaven and most devoutly thank the great Governor of the Universe for producing this turn in our affairs. (Source: Letter to Lucy Flucker Knox, January 7, 1777, in The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, William S. Stryker, 1898)

SAMUEL DeFOREST, Connecticut militiaman—The events of two weeks appears to have rolled on a pivot which has sealed and gave a stamp to the destiny of America. (Source: Samuel DeForest, Military Pension Application Narrative, in The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, John C. Dann, ed., 1980)

NICHOLAS CRESSWELL, English diarist who travelled throughout the American colonies from 1774 to 1777—The minds of the people are much altered. A few days ago they had given up the cause for lost. Their late successes have turned the scale and now they are all liberty mad again. (Source: Nicholas Cresswell: Journal, January 5-17, 1777, in The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence, 1775-1783, John Rhodehamel, ed., 2001)

WILLIAM HARCOURT, Colonel, British Army—Though it was once the fashion of this army to treat [the American soldiers] in the most contemptible light, they are now become a formidable enemy. (Source: Letter to his father, Earl Harcourt, March 17, 1777, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants, Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds., 1967)

CHARLES EARL CORNWALLIS, Lieutenant General, British Army (reportedly responding to a toast at a dinner for British, French, and American officers hosted by George Washington after Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781)—And when the illustrious part that your excellency has borne in this long and arduous contest becomes a matter of history, fame will gather your brightest laurels from the banks of the Delaware than from those of the Chesapeake. (Source: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, William S. Stryker, 1898)

The final quote below is not generally cited in this context but is far better known than the others and VERY MUCH on point.

LAWRENCE PETER “YOGI” BERRA, Professional baseball player, coach, manager, and philosopher—It ain’t over till it’s over. (Source: Attributed to Berra as manager of the New York Mets during the 1973 season and quoted in The Yogi Book: I Really Didn’t Say Everything I Said, Yogi Berra, 1998)

There, now I’ve covered all the bases (so to speak).

Dear Reader:

Please be advised that I anticipate diminished blog production for a period of time (a slowdown, not a complete stop), owing to my immersion in another literary project—a book about the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776 as part of Westholme Publishing’s Small Battles series.

I hope to return to a more regular blogging schedule in the not-too-distant future and extend my sincere thanks to those who have subscribed. To other readers, I hope you’ll consider signing up – it’s free and easy to do in the footer on any page.

Thank you for your indulgence.

Don’t go away. I’ll be back.

Best regards,

dp

SEASON’S GREETINGS, EVERYONE—STAY SAFE AND HEALTHY!!!