Reminder: If you’re reading this in your email, you have to go to dpauthor.com and click on the Speaking of Which tab in order to view the actual blog post with the featured image.

Hi All –

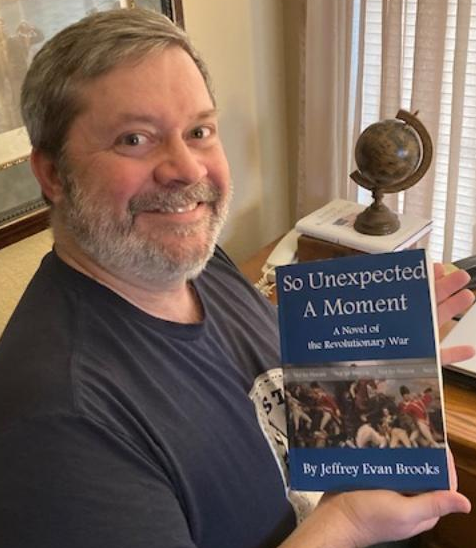

Allow me to introduce Jeffrey Evan Brooks and his new book, So Unexpected A Moment: A Novel of the Revolutionary War, which yours truly had the pleasure of assisting with in terms of reviewing and commenting on the manuscript. To be sure, I found its narrative to be at variance with my interpretive understanding on certain points, but, hey, it IS a novel and I enjoyed the read very much—so much so that I asked Jeff if he would agree to be interviewed for one of my blog posts. He has graciously consented to do so.

Jeff, tell us about your background and how and why you came to write this book.

I am a lifelong student and teacher of history. As a boy, I devoured every history book I could lay my hands on. My parents took me on wonderful road trips, visiting historical sites all across the country. Now that I’m an adult, I buy far too many history books to ever read. And my chosen vocation (I wouldn’t call it a “job”) is to teach American history to 8th graders. History is my life.

As to why I came to write this particular book, I have always found the story of the “Ten Crucial Days” irresistible. It’s simply so full of drama and great characters, with the fate of the nation hanging in the balance. It’s a historical event crying out to be turned into a good historical-fiction novel.

Give us a quick summary of the book’s contents.

The novel is a retelling of the Ten Crucial Days—the Delaware River crossing, the first Battle of Trenton, the critical decisions made by both sides immediately afterwards, the much-neglected Battle of Assunpink Creek (or second Trenton), and finally the Battle of Princeton. Everyone has seen the famous Leutze painting of the Delaware crossing, of course, but as I like to tell my students, the true story is infinitely richer and more dramatic than its depiction in art. There is no need to dramatize it, but what really happened is a more vivid and astonishing story than anything imagined by the best fictional novelist.

But it’s not just a dramatic military tale. The Revolutionary period was a time of new questions about human freedom. If America was going to be an independent nation, what kind of nation was it going to be? So as the protagonists struggle through their various adventures, they find themselves debating with themselves and with one another exactly what the war is really about.

How did the experience of writing this book compare with your previous book, which is an alternate history novel of the Civil War?

The first third of my first novel, Shattered Nation, was genuine historical fiction. It was only with the “point of divergence” that it became alternate history. This book, on the other hand, is straight-up historical fiction. So I did not have the freedom to imagine events unfolding in my own way. I thought this would make the novel easier to write, but I found it was actually much more difficult. I had to do much more intensive research.

And as far as primary source material, the Revolutionary War is not as rich a time period as the Civil War era.

What was most challenging for you in crafting this novel?

As with any historical fiction, there is the problem of accuracy. The needs of the novelist are different from the needs of the nonfiction writer. Sometimes, telling the story with perfect historical accuracy might actually leave the reader more confused than they otherwise would have been. I wanted to tell the true story of the Ten Crucial Days, but not to get so bogged down in details as to leave the reader frustrated and confused. So certain things have gone unmentioned or been simplified, but only in cases so minor as not to make any real difference.

Almost everything depicted is, as nearly as possible as we can determine, what really happened, or at least what could have happened. The adventures of John Mott are largely conjectural, as I needed a vantage point for the reader to see certain events, such as Edward’s Hand’s brilliant delaying action on January 2, 1777. The only point in the novel where I really allowed my imagination to run wild was the story of how Robert Morris obtained the money needed by Washington on December 30, 1776 to pay a bonus to those soldiers who agreed to remain with the army when their enlistments expired, but that story is so steeped in legend that I felt it a worthwhile indulgence.

I decided earlier on that, while the story obviously revolves around Washington, I was not going to use him as a perspective character. I’m not so arrogant as to think I could get inside that man’s head. So it was a challenge to write a novel in which the reader never sees the events through the eyes of the most important person.

What sources of information proved most helpful to you in your research?

The most fun I had doing research for the book was using the free and easily accessible Founders Online, the National Archives’ online database of the writings of Washington and others. Reading the letters and official orders issued by Washington during this period, some of which are included verbatim in the novel, is simply thrilling.

Of the numerous books written about the crossing of the Delaware and the battles at Trenton and Princeton, by far the best is Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer. It’s a stupendous feat of historical writing and fully deserved its Pulitzer Prize. Another very useful source was The Winter Soldiers by the late, great Richard M. Ketchum. I read a number of biographies, including those of Nathanael Greene, Benjamin Rush, Henry Knox, Charles Cornwallis, and others.

And, of course, your wonderful books were a great help to me, especially your book on John Haslet. [Note to the reader: Let the record reflect that no bribery was involved here—at least none that can be proven.]

Did writing this book change your perception of the events or people about whom you wrote and, if so, how?

I felt I already knew a lot about these events when I started to write the novel. But as I wrote, I found myself more and more in awe of these amazing men and what they went through during those ten days. Needless to say, our nation was not created by soft people. It makes me wonder if today’s Americans would have what it takes to match the feats of the founding generation.

At the same time, I found myself admiring the British characters, who were not the cardboard cutout villains Americans sometimes imagine (as, for example, in Mel Gibson’s movie “The Patriot”). General Cornwallis and Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood were great and honorable men, fighting for what they thought was right. And they had a sense of decorum and dignity that has almost entirely vanished in our time and which we would do well to try to restore.

What would you most like readers to take away from reading the book?

This book is an expression of my gratitude and appreciation for the people who created this country. We take our freedoms for granted, so much so that I have 8th graders express astonishment that there are people in the world who don’t have freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to vote, the right to a fair trial, and all the rest. We too easily forget that those who came before us struggled and suffered, and many gave their lives, to win those freedoms for us. David McCullough once commented that not bothering to learn about the founding generation is a form of ingratitude and that ingratitude is a shabby personal quality. I entirely agree.

Do you have another writing project in mind?

I am thinking of writing a novel about Operation Dragoon, the little-known invasion of southern France during World War II.

Thanks, Jeff. Good luck with the new book and your next undertaking.

And if readers want to check out your Amazon page, they can do so here.

BTW, in case anyone is wondering, the official release date for my new book, Winning the Ten Crucial Days, is April 15, although signed copies are currently available in the gift shop at Washington Crossing Historic Park.