August 27 marks the 245th anniversary of the Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn. This was the first major battlefield contest of the Revolutionary War and by some accounts the largest during the entire conflict—with some forty thousand troops involved if one includes naval personnel—as well as one of the worst defeats suffered by the Continental army.

Almost Up the Creek

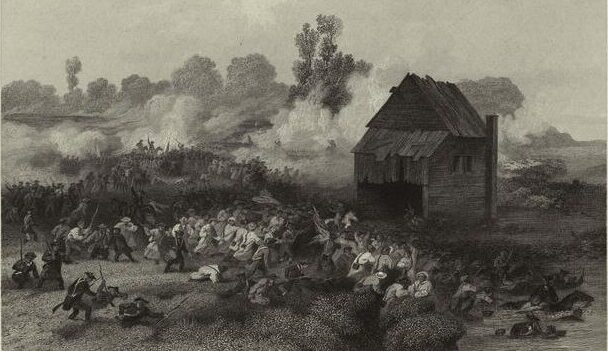

The image above is from a print based on the 1858 painting by Alonzo Chappell entitled The Battle of Long Island (NYPL Digital Collection). It depicts the heroic stand by Lord Stirling’s brigade along the Gowanus Road during this engagement. The Maryland and Delaware regiments, with their backs to the Gowanus Creek, held off a much larger enemy force long enough to save the Continental Army from a catastrophic fate. According to some accounts, their holding action prompted General Washington to laud them as his “brave fellows.” And those Maryland and Delaware soldiers who eluded the enemy were forced to take the one barely possible escape route available in their desperate situation—swimming across the widest portion of the Gowanus Creek, with the tide flowing in. They were only able to do so because some 400 Marylanders under Lord Stirling—General William Alexander—who were heavy outnumbered and surrounded by the enemy, launched a heroic attack that bought time for the rest of the brigade to make it across the creek.

The Outcome

The determined resistance by Stirling’s brigade was a significant factor in allowing about half the American troops engaged in the battle to reach the safety of their fortifications on Brooklyn Heights rather than being entrapped by the overnight enemy flanking maneuver through the largely unguarded Jamaica Pass that dictated the outcome of this contest. As a result, the plan of attack adopted by General William Howe, the British army’s commander (and devised by his subordinate, General Henry Clinton) yielded a brilliant tactical success but failed in its strategic objective of destroying the rebel force.

The Continental army counted the losses from its defeat at about 300 killed and 1,100 captured but had no reliable estimates of the number wounded. British figures in regard to their casualty count have been regarded as fairly precise, with General Howe reporting just under 400 casualties.

In his first major battlefield engagement as a commanding general, Washington blundered dreadfully. He left roughly half his force on Manhattan Island, which meant he was opposing a superior foe with only about half his strength. After General Nathanael Greene took ill, Washington changed commanders on Long Island twice in one week just before the battle. He failed to ensure his generals were familiar with the terrain they were defending. And early on, he dismissed a large component of his cavalry (the volunteer Connecticut Light Horse, not wanting to pay for the upkeep of their mounts and insisting they serve as infantry) who could have provided him with the scouts he needed to surveil redcoat maneuvers, especially that overnight march through the Jamaica Pass. Leaving such a critical route largely unguarded was probably the worst of Washington’s errors, as it exposed the army’s left to a flanking move that would have had catastrophic repercussions but for the heroics of Stirling’s men.

Washington arguably atoned for his inept performance two days later. On the night of August 29-30, some 9,500 American soldiers, their horses, and most of their equipment evacuated across the East River from Brooklyn to Manhattan. A mere three stragglers, who could not resist the temptation to loot, were captured on Brooklyn Heights. Washington, who rescued all but five of his cannons, left with the last of the troops. He had lost Long Island but saved his army in one of the most skillful evacuations in military history, conducted at night in small craft on difficult water and undetected by a numerically larger enemy and its imposing fleet. Of course, this maneuver was mightily assisted by the elements: high winds that precluded the British fleet from moving up the Hudson River just prior to and during the August 27 battle; then a storm that engulfed Manhattan and Brooklyn for two days and further stymied the Royal Navy; and finally a thick fog at dawn on August 30 that provided a protective cloak for Washington’s withdrawal across the river.

Some Observations

Delaware Lieutenant Enoch Anderson may have spoken for many a Continental soldier after the Long Island debacle: “A hard day this, for us poor Yankees! Superior discipline and numbers had overcome us. A gloomy time it was, but we solaced ourselves that at another time we should do better.”

From her home in Braintree, Massachusetts. Abigail Adams informed her husband John, serving with the Congress in Philadelphia, of what news had reached the home front: “We Have had many stories concerning engagements upon Long Island this week, of our Lines being forced and of our Troops retreating to New York. Perticuliars we have not yet obtaind. All we can learn is that we have been unsuccessfull there . . . . But if we should be defeated I think we shall not be conquered. A people fired like the Romans with Love of their Country and of Liberty a zeal for the publick Good, and a Noble Emulation of Glory, will not be disheartned or dispirited by a succession of unfortunate Events. But like them may we learn by Defeat the power of becoming invincible.”

In writing to Congressional president John Hancock on September 8, the Continentals’ commander-in-chief anticipated General Howe’s next move: “It is now extremely obvious from all Intelligence—from their movements, & every other circumstance that having landed their whole Army on Long Island (except about 4,000 on Staten Island) they mean to inclose us on the island of New York.” The impulse to avoid this predicament would force the rebels to abandon Manhattan, albeit not for several weeks, and engage the enemy further north in Westchester County, in the next phase of the New York campaign. Washington would be extremely fortunate during this period in at least one respect: the British commanding general was even slower to take action than he. And Howe!