Dear Reader:

Happy New Year.

Please note: For those of you who are new subscribers (and those who aren’t), if you’re reading this in your email, you have to click on the link to my website and then on the Speaking of Which tab in order to view the actual blog post with the featured image.

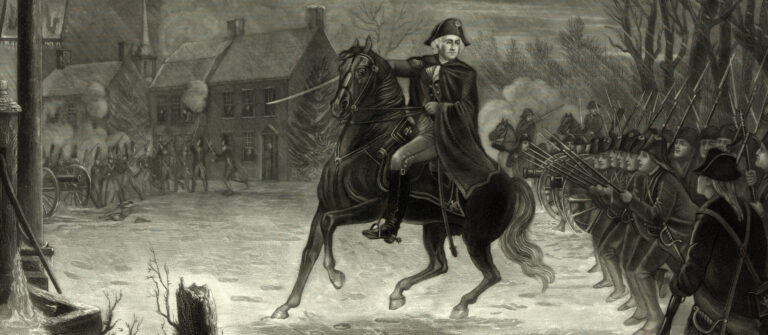

This post and the next will outline the fate of various officers in the respective armies after the Revolutionary War. We’ll start with an admittedly arbitrary and very select list of Continental Army officers presented alphabetically below. The next post will attempt to do the same for several British officers who played leading roles in the conflict.

William Alexander (Lord Stirling): The brigadier general who commanded a Continental Army brigade during the “Ten Crucial Days” winter campaign of 1776-1777 was considered one of George Washington’s most loyal officers. He was too ill to participate in the battles at Assunpink Creek and Princeton but was promoted to major general early in 1777 and saw action at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. Known for eating and drinking to excess, he died from gout in Albany, New York, at age 56 in 1783.

John Cadwalader: The colonel of the Philadelphia Associators was appointed brigadier general of the Pennsylvania militia in 1777 but declined Continental Army appointments to brigadier general and to brigadier and commander of the cavalry. In 1778, he left military service and returned to his family’s estate in Shrewsbury, Maryland. That year, he fought a duel with Washington’s nemesis, Thomas Conway, over the latter’s alleged “cabal” among certain army officers against Washington’s leadership, inflicting a nonfatal wound on Conway. After the war, Cadwalader moved from Pennsylvania to Maryland and served in its House of Delegates. He died in Shrewsbury at age 44 in 1786.

John Glover: The colonel commanded the seafaring men of the 14th Massachusetts Continental Regiment from Marblehead, who played an indispensable role in the Delaware River crossing of December 25, 1776. He was left without a regiment after December 31, 1776 because of expired enlistments. Glover went home to attend to family and business matters after his regiment disbanded but returned to the army in 1777 and served for the remainder of the war. He died in Marblehead at age 64 in 1797.

Nathanael Greene: The major general who led one of Washington’s two divisions during the “Ten Crucial Days” subsequently became quartermaster general of the Continental Army. He later earned fame as the successful commander of the southern army against General Charles Earl Cornwallis, in which role he was credited with waging a brilliant military campaign against a superior foe. After the Revolution, Greene was awarded liberal grants of money by South Carolina and Georgia and settled on an estate near Savannah in 1785. He died there at age 43 in 1786.

Alexander Hamilton: The young artillery captain early in the war became an aide-de-camp to Washington with the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1777 and proved to be of inestimable value in his services to the commander-in-chief. He attained battlefield glory by leading the assault on British redoubt number 10 at Yorktown in 1781, then returned to New York City where he practiced law and entered politics. Hamilton supervised and co-authored The Federalist Papers with James Madison and John Jay in 1787 in support of the proposed federal constitution. As Washington’s secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795, he played an essential role in shaping young America’s national government and facilitating the development of its capitalist economy, while emerging as the leading spokesperson for the political faction known as the Federalists. He died in New York City in 1804, at the age of 49, from a mortal wound sustained in a duel with his bitter political rival, Aaron Burr.

Edward Hand: The colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, who was promoted to brigadier general in 1777 and became the Continental Army’s last adjutant general, returned to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, at war’s end and later built Rock Ford, a Georgian-style brick mansion on several hundred acres of land. He lived there from 1794 until his death. Hand practiced medicine, served as a member of the Congress of Confederation (1784-1785) and the Pennsylvania Assembly (1785-1786), and later as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention (1790). Tradition has it that he played host to Washington during the latter’s visit to Lancaster as president in 1791. He died in Lancaster at age 57 in 1802.

Henry Knox: The Continental Army’s artillery commander and brigadier general for most of the war was promoted to major general in 1782 and succeeded Washington as the army’s commander-in-chief in 1783, serving briefly in that position. Having been at Washington’s side during every battle, Knox became the nation’s first secretary of war under President Washington and then retired to his estate in Maine in 1795. He died there at age 56 in 1806 as the result of an infection from a chicken bone that lodged in his throat.

Charles Lee: The major general who was Washington’s second in command when captured by the British in December 1776 was returned in a prisoner exchange in the spring of 1778. He led the Continental Army’s vanguard against the enemy at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, when he was humiliated in a battlefield confrontation with Washington. A court-martial that Lee requested to clear his name found him guilty of insubordination, and he was dismissed from the army in 1780. He lived as a recluse in retirement, first on his Virginia estate and then in Philadelphia, where he died alone in a tavern at age 51 in 1782.

Thomas Mifflin: The general persuaded the soldiers of a New England regiment to remain with the Continental Army when their enlistments expired on December 31, 1776, by offering each a financial bonus for agreeing to serve another six weeks, and thereby inspired Washington to do the same when appealing to other units. Mifflin had been a Philadelphia merchant and politician who served as a delegate to the Continental Congress before joining the army. He rose through the ranks to become a major general but experienced tensions with Washington over Mifflin’s handling of his duties as the army’s first quartermaster general. After his military service ended, he again served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and subsequently as a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. He became the first governor of Pennsylvania in 1790 and served for nine years. Mifflin died in Lancaster at age 56 in 1800.

James Monroe: The lieutenant who was wounded at the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776 saw further military service and after the war returned to his native Virginia. He went on to enjoy an illustrious political career, becoming a United States senator, governor of Virginia, ambassador to France, secretary of state and war, and finally the fifth president of the United States (1817-1825). He is best known for asserting, in his annual message to Congress in 1823, the “Monroe Doctrine” that declared opposition to European intervention in the Western Hemisphere, which became a cornerstone of American foreign policy. He died in New York City at age 73 in 1831.

Joseph Reed: The lawyer and colonel who served as the Continental Army’s adjutant general (chief administrative officer) during the “Ten Crucial Days” was offered both a position as brigadier general and as chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1777, but he turned both down because he had been elected to the Continental Congress. In 1778, he was elected president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania (equivalent to the position of governor) and in that position oversaw the enactment of a 1780 law providing for the abolition of slavery in Pennsylvania. Reed died in Philadelphia at age 43 in 1785.

Arthur St. Clair: The Continental Army brigadier general may have been the first officer to suggest to Washington the idea of an overnight march from Trenton to Princeton on January 2-3, 1777. He was promoted to major general in 1777 and later fought in the southern theater. St. Clair left the army in 1783 and became a delegate to the Continental Congress. He served as governor of the Northwest Territory from 1787 to 1802 and, during a brief return to military duty, suffered a severe defeat against Native American tribes at the 1791 Battle of the Wabash. He died in Pennsylvania at age 82 in 1818.

John Sullivan: The major general who led one of Washington’s two divisions during the “Ten Crucial Days” commanded American troops fighting against the Native American tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy and their Loyalist allies later in the war. After the Revolution, the New Hampshire-born attorney served as attorney general and governor of his state and as a federal district judge. He died in Durham, New Hampshire, at age 54 in 1795.

George Washington: The Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army resigned his commission when the war ended in 1783 and returned to his estate at Mount Vernon in Virginia, but was later recalled to public service. He presided over the 1787 convention in Philadelphia that adopted the federal constitution and became the first President of the United States in 1789. In that role, he forged the federal government’s executive branch, established a set of enduring precedents that would guide his successors—perhaps most importantly creating a tradition of presidential term limits by refusing to serve for a third term—and spearheaded the effort to convert the promise of constitutional democracy into a living reality. Washington retired from public life in 1797, returning once again to Mount Vernon. In what is known as his farewell address to the American people upon leaving the presidency, he exhorted his fellow countrymen to assume a greater sense of national identity in their capacity as citizens of the United States. Washington died at Mount Vernon at age 67 in 1799.

William Washington: The captain and distant cousin of George Washington was wounded at the first Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776 and earned a promotion to major and then colonel. He distinguished himself as a cavalry officer in the southern theater and received a silver medal from Congress, one of only 11 awarded during the war, for his role at the Battle of Cowpens in 1781. After the Revolution, Washington settled in South Carolina and served in the state legislature. He died at age 58 in 1810.